For Behind the Screen : The Hidden Masters of the Golden Age of Filmmaking, our continuing series of profiles on the men and women who worked behind the cameras, we have chosen to aim the spotlight on Helen Rose, an extremely talented costume designer of the 1940s-1960s. Since the Oscars are approaching, our choice is especially apropos considering Helen Rose was nominated for no less than ten awards for Best Costume Design, including The Merry Widow ( 1952 ), Executive Suite ( 1954 ), and I'll Cry Tomorrow ( 1955 ).

Like her fellow female associate, Edith Head, Helen Rose had risen from staff designer to become chief costume designer of a major film studio. Head worked at Paramount and Irene at Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer up until 1949, when she left the studio. Shortly thereafter, Helen Rose became the new chief designer. Her style was elegant and innovative, and some of the dresses she created were the most beautiful seen on film.

Helen Rose began designing stage and nightclub costumes when she was but 15 years old for the Lester Costume Company who specialized in costumes for vaudeville. In the late 1930s she was hired as head designer for the skating spectaculars, the Ice Follies.

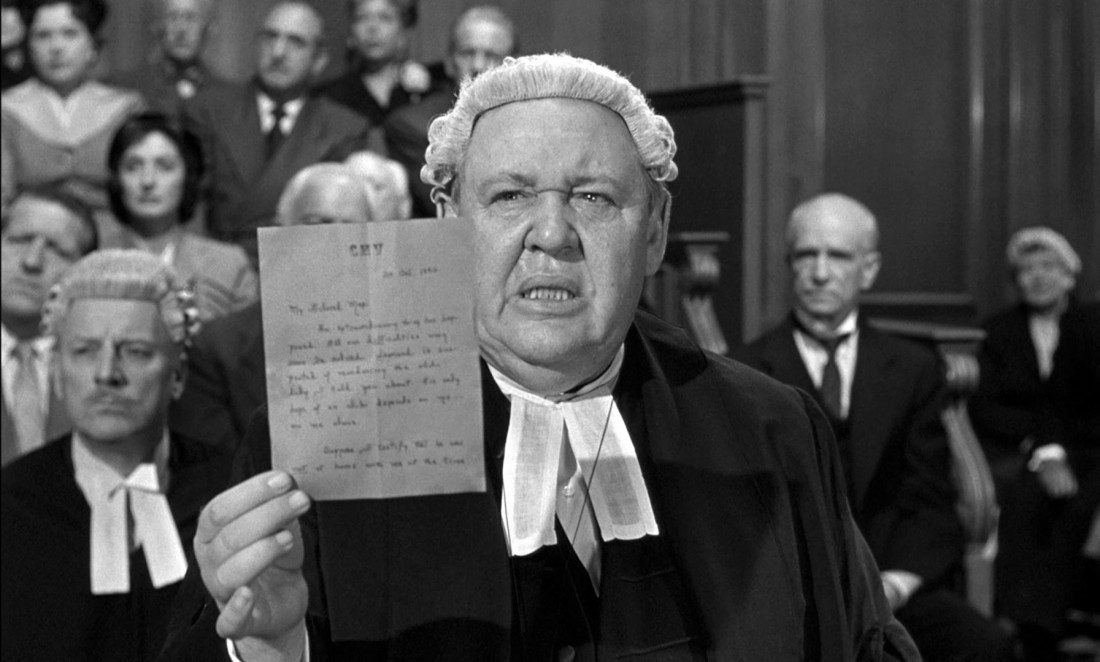

|

| Love Me or Leave Me |

It was in 1941 that she was hired to create costumes for musicals over at Twentieth Century Fox. This tenure lasted only two years, when Louis B. Mayer beckoned her into the lion's den at MGM. Their chief designer, Adrian, had resigned and the studio was looking for fresh talent in their wardrobe department. Helen Rose assisted Irene for the next five years, helping work on such productions as Two Sisters from Boston ( 1946 ), Till the Clouds Roll By ( 1947 ), The Courage of Lassie ( 1946 ), Cynthia ( 1947 ) and Julia Misbehaves ( 1947 ).

MGM was churning out musicals, comedies, and dramas in such quantity during the late 1940s to satisfy the demands of post-war audiences that, even though Irene was still head of the costume department, Helen Rose had a chance to exercise her creative couture skills in a number of fine productions.

For The Harvey Girls ( 1946 ), Rose designed a plethora of beautiful period gowns. In addition to the traditional waitress wardrobe of the Harvey girls, Judy Garland sported over seven different outfits including a cream-colored puffed-sleeved dress, a wedding gown, a light-blue chiffon nightgown, and a lovely white ballgown with ruffled tulle on the shoulders. However, it was Angela Lansbury, as feisty saloon gal Em, who wore the most eye-popping Technicolor creations. The golden gown Rose created for Em, studded with beads, deserved an Oscar nomination in itself but, unfortunately, the entire film was overlooked for the costume design category. Oddly enough, almost all of the films that showcased Helen Rose's best work were overlooked.

In The Unfinished Dance ( 1947 ), Rose designed not only the principal actors' wardrobe but many of the ballerinas dresses as well. Mademoiselle Ariane Bouchet ( Cyd Charisse ) was the prima-donna ballerina who wore fashions as chic as her name. One of the most memorable gowns she wore was a velvet dress ( which fetched $2,750 during Debbie Reynolds' major wardrobe auction in 2014 ).

|

| The velvet gown seen in The Unfinished Dance ; Good News |

For Good News ( 1948 ) Helen Rose help transport audiences back into the roaring 1920s with her authentic college garb of the period.

Annie Get Your Gun ( 1950 ) was another career highlight for Helen Rose. The western costumes that Betty Hutton wore combined the bright colors of the 1950s with the rugged utility that the real Annie Oakley would have needed as a sharpshooter touring across the world with Buffalo Bill's Wild West Show. Rose's designs were undoubtedly inspiration for much of the western wear for men, women, and children that were sold in catalogs throughout the decade.

Helen Rose had a knack for creating costumes that perfectly suited the style of the wearer. Jane Powell's dainty hourglass figure was emphasized in the dresses she wore in A Date with Judy ( 1948 ), Luxury Liner ( 1948 ), Nancy Goes to Rio ( 1950 ) and Two Weeks with Love ( 1950 ).

Lana Turner had a figure all women would envy and her petite height made her an ideal model for below-the-knee skirts and dresses. For The Merry Widow ( 1952 ) and Latin Lovers ( 1953 ), Rose designed some beautiful Spanish-inspired evening gowns. Years later, for Bachelor in Paradise ( 1961 ), Turner wore Helen Rose creations again...and surprisingly, her glam figure was unchanged!

|

| Period costumes from Two Weeks with Love |

Esther Williams created many of her own swimsuit designs when she launched her own swimsuit company, but during her reign at MGM, she and Helen Rose worked together to create swimwear that looked stunning both wet and dry. Duchess of Idaho, Pagan Love Song, Texas Carnival, Million Dollar Mermaid, Easy to Love and Dangerous When Wet all featured costumes designed by Rose.

The costumes seen in Father of the Bride ( 1950 ) were also some of Rose's best work. Elizabeth Taylor adored the wedding gown that she wore in the film so much that she asked Helen Rose to design her wedding gown for her marriage to Nicky Hilton that same year.

Grace Kelly was another great admirer of Rose's sophisticated taste. She wore Rose creations in Mogambo, High Society, and The Swan, and like Taylor, also hired Rose to design her wedding gown. Over 25 yards of vintage Brussels rose point lace and silk faille was used in the gown, and it was a creation that was admired the world over.

Elizabeth Taylor's wedding dress was less memorable, but the simple and elegant white chiffon Grecian gown that she wore in Cat on a Hot Tin Roof ( 1958 ) became an iconic dress. That same year Rose launched her own label featuring ready-to-wear clothing accessible to the public through high-end department stores such as Bonwit Teller, Marshall Fields, and Joseph Magnin. Some of her more simple designs were also available as patterns distributed through Advance and Spadea.

Chiffon was Helen Rose's material of choice and she especially liked the way it moved and picked up light. An example of one of her most beautiful chiffon dresses was the simply white ensemble worn by Shirley Jones in The Courtship of Eddie's Father ( 1963 ). Dina Merrill also wore a gorgeous light blue chiffon dress in the same film, as well as this elegant business "suit".

|

| Dina Merrill and Shirley Jones in The Courtship of Eddie's Father |

During the 1960s, Debbie Reynolds fashioned some of the best of Rose's creations in The Gazebo ( 1959 ), and Goodbye, Charlie ( 1964 ). Helen Rose probably never realized that so many of the dresses, gowns, and suits she designed for actors in all of those MGM films would end up in Reynolds' personal collection of costumes.

|

| Goodbye, Charlie! ( 1964 ) |

In 1966, Helen Rose left MGM to open up her own design business, catering to wealthy clients. She also kept busy writing a fashion column and penning two books, one being her autobiography "Just Make Them Beautiful"....a fitting title, for that's just what she did.

This post is our contribution to the

31 Days of Oscar blogathon being hosted by

Paula's Cinema Club,

Outspoken and Freckled, and

Once Upon a Screen. Head on over to any of these sites to read more about the actors, films, and craftsman who were awarded Academy Awards.

To read more profiles in our

Behind-the-Screen : The Hidden Masters of the Golden Age of Filmmaking, click

here!